Initial Thoughts on Kojève and Dante

On the 'serious comedy' of human life, comedic catharsis, Love, and our telos

“Human life is a comedy-one must play it seriously.”

- Alexandre Kojève

“As the geometrician, who endeavours

To square the circle, and discovers not.

By taking thought, the principle he wants,

Even such was I at that new apparition;

I wished to see how the image to the circle

Conformed itself, and how it there finds place;

But my own wings were not enough for this,

Had it not been that then my mind there smote

A flash of lightning, wherein came its wish.”

-Dante Alighieri, Canto 33, Paradiso, Divine Comedy, trans. Longfellow

Upon my initial reflections after (somewhat simultaneously) reading both, it seems to me that Alexandre Kojève and Dante Alighieri each recognize that human life is a type of ‘serious comedy.’ It is in answer to this, as an attempt at ‘comedic catharsis,’ that they offer us their two distinct but perhaps overlapping teleologies of human ‘progress.’

For Kojève, human progress is material and linear, the comedic catharsis lies at the ‘end of history’—the ideal citizens mutually recognize each other in a truly universal yet benevolently authoritarian order. Kojève’s Hegelian teleology as applied to actual humans, demonstrates that the master-slave dialectic (the recognition and struggle between two ‘self-consciousnesses’) is unstable in real life—to truly recognize the consciousness of the other is a freely-willed and unconstrained decision, which is impossible for the ‘slave’ to make, by definition. For this reason, in the material realm, the telos (“final analysis”) of the Hegelian dialectic must be its own sublation into human beings’ equal and mutual recognition of each other, thus ending the master-slave relationship and bringing about a new true ‘citizen.’1 Here, it is worth pausing to underscore that the word sublation (German: ‘aufheben’) is best defined as a process of purification;2 and catharsis (Ancient Greek: κάθαρσις) in theatre and medicine is also defined as a sort of purification/purgation through release!3 Therefore, it seemed fitting to me to understand Kojève’s sublation of the master-slave dialectic at the end of history as a type of comedic catharsis to the serious comedy of human life.

Since there is still the necessity of a sovereign in any regime, Kojève also argues that even this ‘final’ regime will require benevolent authority, to which each citizen can freely recognize and ‘submit’ to for the greater good. Interestingly in some ways, it can be argued that Kojève’s vision is an affirmation of a sort of ‘love of other’ that lies at the end of all things (free recognition of each other is a type of love). This ‘recognition-love’ is then properly ordered in society by a benevolent authority—which is not the same as ‘love,’ but a necessary feature of even this last regime. It is unclear, at least based on my initial (and limited) readings, whether Kojève’s version of ‘love’ could be anything beyond mutual recognition grounded in linear time, since the question would naturally arise: Where would transcendent love beyond the needs of the temporal self come from? Kojève’s atheist and materially-rooted philosophy does not, and perhaps need not answer this question to remain applicable for us as a possible model for earthly regimes.

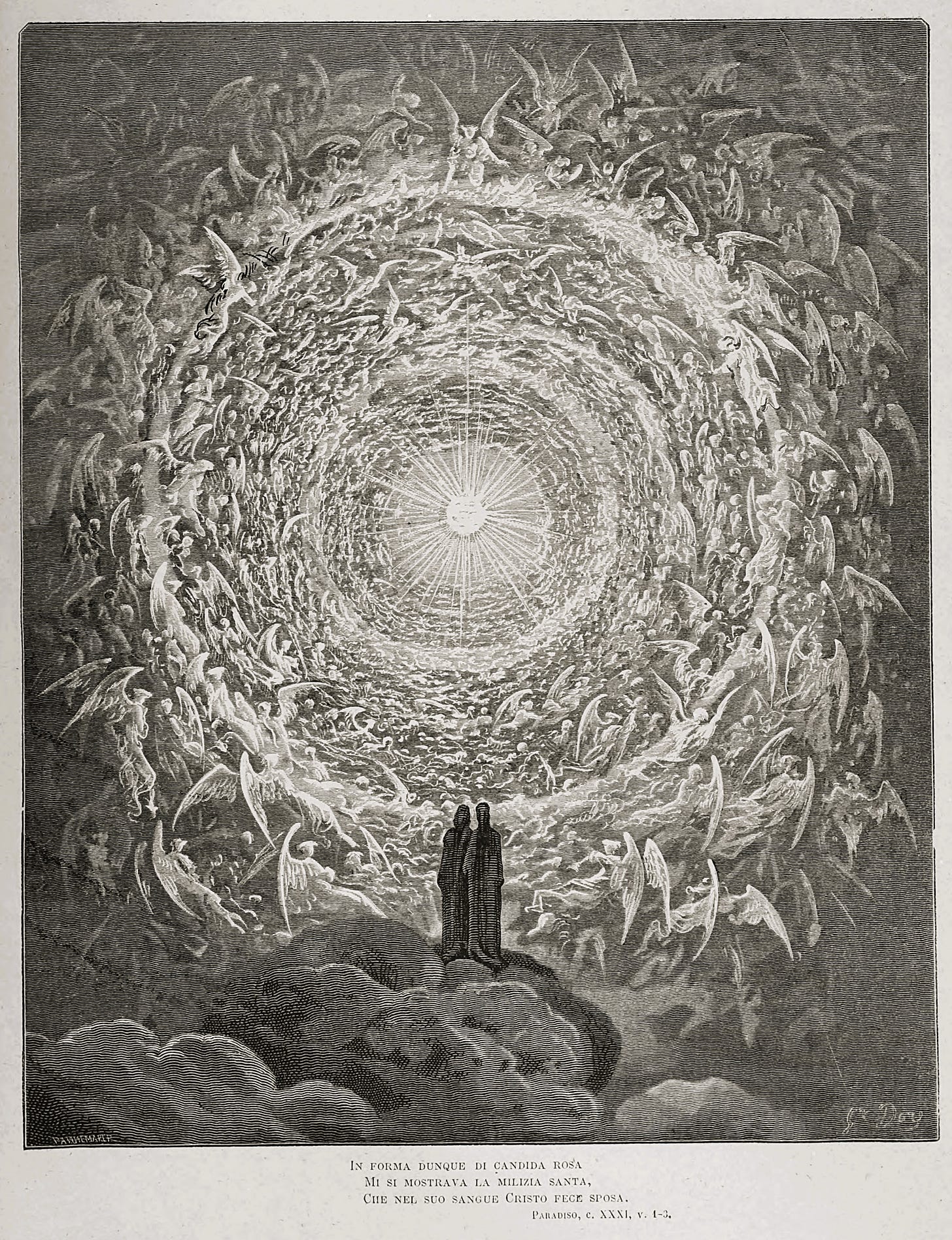

Many centuries before Kojève, Dante, also treating life as a (divine) ‘serious comedy,’ explored his own comedic catharsis as a teleology of Love and benevolent authority. Again, the term comedic catharsis is apt for use, since its ‘purification’ connotations quite literally apply to Dante’s exploration of salvation through purgation. For Dante like Kojève, human progress begins in the material world (earthly deeds matter), but progress is also ascendent beyond the material4 and beyond linear time. Dante’s comedic catharsis lies not only in the earthly realm but also in the spiritual, i.e. the beatific vision, which, by purgation, takes into itself both that which is absurd and that which is rational.5 Unlike Dante, however, Kojève clearly stated that he grounds his end of history and its catharsis only in our temporal lives. Given this, I think that Kojève pushes the limits of teleological philosophy as far as possible to arrive at his telos of the final human (purified by ‘recognition-love’). Dante, on the other hand, by virtue of being Christian, must reckon with both what is earthly and what is divine.

It is important to note that Dante does not discount the power of rational philosophy, after all his guide for much of the Divine Comedy is Virgil, a pagan. Both Inferno and Purgatorio are also set on earth, which I suggest is Dante recognizing the necessity of material teleology to an extent. It is only at the end of Purgatorio and the start of Paradiso that Dante is reunited with Beatrice (from the Latin: beatus, ‘blessed’) who alone, as an embodiment of his unconditional Love (see footnote 4), can now guide him beyond philosophy and make transcendent his teleology—by transforming the telos of his Love itself beyond a temporal telos of ‘recognition-love.’6 Just as with Kojève’s end of history, Dante’s beatific vision at the end of the Divine Comedy is also a sort of cathartic universal ‘regime,’ operating under a benevolent authority that humans have freely recognized and submitted to (Christ is “Lord of lords and King of kings,” Revelation 17:147). The difference between Kojève and Dante, of course, being that the former deals with a material telos alone whereas the latter necessarily must also consider the transcendent telos.8 Yet, it is clear that both Dante and Kojève note the importance of some type of ‘universal purification’ under benevolent authority at the end of all things, even as their understandings of the role of Love/recognition differ.

Although much more remains to be explored, in this short essay I suggest that both Kojève and Dante, by embracing the ‘serious comedy’ of human life, seek its ‘comedic catharsis’—the former in the material realm and the latter in both the material and divine realms. What strikes me in their respective attempts, is that they both develop a teleology that deals with the questions of universality and benevolent authority, and perhaps most interestingly, how both these questions relate to freely willed ‘love’ (see footnote 8). I will finally add that, as of right now, I’m not sure if or how their two visions could be synthesized or sublated in modern regimes… Constitutional monarchism? Secular ‘authoritarianism’ with Christian characteristics? A republic with a clearly-defined Christian common good? Whatever the ‘synthesis,’ it would need to separately account for both recognition and transcendent Love… Perhaps this is not possible and we’re actually faced with a dichotomy, but it is the nature of dialectics to at least ask these questions as they arise in one’s mind!

(Note 1: Every text referenced in this piece is available for free online, and has been linked in the footnotes.)

(Note 2: These thoughts are my initial conclusions that I might add to/rework later with more feedback and reading. Last edited: 11/17/2024)

See: Alexandre Kojève, Chapters 2 & 7, Introduction to the Reading of Hegel; and Alexandre Kojève, Part B., Notion of Authority

The translation and meaning of the original word ‘aufheben’ from Hegel’s German is fraught. I, borrowing from some Hegel scholars, define it here as the clashing of contradictory ideas that yields something both synthesized and purer than the original two, such as through a chemical process like evaporation and distillation.

See: The definition of catharsis (κάθαρσις) both in Ancient Greek and in English usage.

A Christian development of the Platonic ascent of Love.; See: Plato’s Symposium; Christians synthesized the Greek ideas of Love and understood Love as being of four main different types: ἔρως (‘Eros,’ sexual-love), φιλία (‘Philia,’ friendship-love), στοργή (‘Storge,’ familial-love), and ἀγάπη (‘Agape,’ selfless-love). These are distinct, yet often relate to and transform each other, with Agape being the highest Love that can contain all others within it (see: C.S. Lewis, Four Loves). In the Divine Comedy, for example, Dante’s Eros for Beatrice in life is not only maintained but also ‘sublated’ into Agape as they ascend in Paradiso together.

See: Dante Alighieri, Paradiso, Divine Comedy

For Beatrice’s correction of Dante’s understanding of Love, see: Dante, Canto 33, Purgatorio, Divine Comedy

Heaven is clearly depicted as a sort of ‘monarchy’ in: The Holy Bible, New Testament, Revelation 17:14

Is Christian teleology-turned-theology the harder task? It seems to me that the atheist philosopher can choose to limit himself both to language (with the risk of nominalism) and to ‘rationality.’ However, any serious Christian thinker, is obligated to inquire simultaneously about both earthly philosophy and the transcendent nature of God (see: Josef Pieper, The Philosophical Act). This more complex ‘mixed’ inquiry is ‘theology,’ which itself reaches its own limits, since the fullness of Divine Mystery remains ineffable, except when understood as the highest order of Love. Love (Agape) in Christianity is traditionally that which we can both attempt to speak of/know and that which exists in silence beyond language (c.f. the life of St. Anthony of the Desert; Gregory Palamas on hesychasm; and more). Dante himself recognizes this paradoxical nature of comprehending Christian Love, calling it to “square the circle” in Canto 33 of Paradiso, quoted above. Kojève, for his part, also discusses this ‘silence’ problem of Christian mysticism (see: Kojève on mysticism), although I would argue he doesn’t fully reckon with Love as ‘both knowable, and silent’ as I stated, or how this could enrich his own version of love (understood as recognizing each other, but not also as looking upward together)… However, Kojève doesn’t have to address this last point since he is a philosopher, not a theologian. Indeed, his brilliance lies in how he tests the limits of teleological philosophy as it relates to the material world. The onus remains on the Christian to be receptive to that which is beyond (and lovingly, if imperfectly, share this with others).